Christian Aid Church Land Programme: South Africa apartheid and climate change immersive experience.

Location: Pietersburg Durban, South Africa

From 9-16 October 2022, I was invited to represent Churches Together in England’s Racial Justice Working Group at the Christian Aid and Church Land Programme’s South African apartheid and climate change immersive discernment experience. These are my personal reflections, which include some recommendations for ecumenism in England.

The main purpose of this seven-day experience was to build international ecumenical relationships and to observe and harness best practice about the church’s role in resisting racial and climate inequality whilst standing in solidarity with the poor.

The first day of our encounter with our international partners consisted of setting the scene and our expectations. This experience would be about discernment, finding new ways of articulating meaning around justice issues, resisting western normativity in knowledge production and honouring African epistemology and context.

We were also encouraged to lay down our institutionalisms, and to disengage with emails, social media and anything that would compete for our attention, so that we could be fully emersed in our context. This was a liberating way of engaging with the world and I was struck by the space that became available to engage with the environment and build genuine non-transactional relationships. This counter-cultural space reflected the beauty of ecumenism, which at its best creates space for deep observation, relationship, learning and receptivity. We need to ensure that these characteristics are not buried under bureaucracy – whilst it’s important to have structures and programmes, their ultimate purpose should be to facilitate relationship.

We were also told that we would be embarking on an “Oujumah”, the South African word for journey, and that answers would be found by walking the path. This powerful statement encouraged the group to reflect on their individual justice contexts, and to resist quick fix mentalities towards dismantling injustice, as these lead to a moment instead of a movement. The group was also reminded that to stand in true solidarity with those affected by injustice would mean walking alongside their journey, giving space for them to be the professors of their own stories and to challenge any communal or individual benefit from another community’s oppression.

The theory of change and justice methodology that underpinned our process was:

- See

- Judge

- Act

According to this methodology, to see allows for specific identification of the issue and root cause of injustice, to judge allows for reflection, research, collaboration and planning towards solutions, and then you act. Here, action comes from an informed place, helping with sustainability and stopping reactionary-based responses which lack depth and ultimately damage communities.

Before analysing what I saw, judged and recommend as actions, it is important to understand our South African host and partners, The Church Land Programme.

The Church Land Programme

The Church Land Programme (CLP) is an independent non-profit organisation that works through a process of animation with groups of poor people, to create unique responses to their unique situations.

CLP was initiated in 1996 as a joint project between the Association for Rural Advancement (Afra) and the Pietermaritzburg Agency for Christian Social Awareness (Pacsa), in response to the land reform process taking place in South Africa. It was established as an independent organisation in 1997 and initially focused on church-owned land, while also challenging the church to engage in the national land question and work for a just and sustainable agrarian transformation.

The 2004 strategic planning process opened a new direction for CLP, giving focused attention to practice and reflection on practice. This has had a profound affect on the manner in which CLP approaches its work, leading to an open-ended commitment to “walking with communities towards the realisation of the choices that they make’. CLP thus opened itself to the politics of the poor, and its practice is guided by an active solidarity with people in the struggles that they define and take forward on their own terms.

CLP also broadened its focus to take in the relationship of people-land-church; taking up people’s issues in relation to land – whether rural or urban – and interrogating the relationship of the church to those issues – whether the local church of the people themselves or the institutional church.

In 2007, CLP identified animation as its core practice. This involves an iterative process that applies the learning and action cycle in people’s specific situation,s and with the intention that they mobilise themselves to act to change that situation in ways that they decide. CLP has a clear and firm organisational commitment to this core practice. Consequent to this, it is people’s movements, organised groups of the marginalised, and those acting in solidarity from within institutional spaces who are the key groups with whom CLP interacts.

See

South Africa’s political and racial context

South African apartheid, which in South African Afrikaans means “separateness” and “aparthood”, was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s.

Apartheid was characterized by an authoritarian political culture which ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation’s minority white population. According to this system of social stratification, white citizens had the highest status, followed by Indians and Coloureds, then Black Africans.

On a broad level, apartheid was categorised into petty apartheid, which entailed the segregation of public facilities and social events, and grand apartheid, which dictated housing and employment opportunities by race. The first apartheid law was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, 1949, followed closely by the Immorality Amendment Act of 1950, which made it illegal for most South African citizens to marry or pursue sexual relationships across racial lines.

The Population Registration Act, 1950, classified all South Africans into one of four racial groups based on appearance, known ancestry, socioeconomic status, and cultural lifestyle: ‘Black’, ‘White’, ‘Coloured’, and ‘Indian’, the last two of which included several sub-classifications. Places of residence were also determined by this racial classification. Between 1960 and 1983, in some of the largest mass evictions in modern history, 3.5 million black Africans were removed from their homes and forced into segregated neighbourhoods as a result of apartheid legislation. Most of these targeted removals were intended to restrict the black population to ten designated “tribal homelands”, also known as Bantustans, four of which became nominally independent states. The government announced that relocated persons would lose their South African citizenship as they were absorbed into the Bantustans.

Apartheid sparked significant international and domestic opposition, resulting in some of the most influential global social movements of the twentieth century. It was the target of frequent condemnation from the World Council of Churches and the United Nations and brought about extensive arms and trade embargoes on South Africa during the 1970s and 1980s.

Internal resistance to apartheid became increasingly militant, prompting brutal crackdowns by the National Party government, and protracted sectarian violence which left thousands dead or in detention. Some reforms of the apartheid system were undertaken, including allowing Indian and Coloured political representation in parliament, but these measures failed to appease most activist groups.

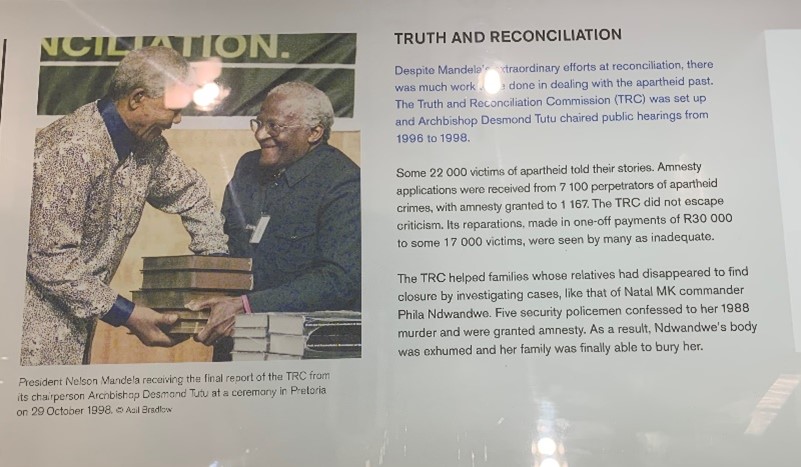

Between 1987 and 1993, the National Party entered into bilateral negotiations with the African National Congress (ANC), the leading anti-apartheid political movement who were demanding an end to segregation and the introduction of majority rule. In 1990, prominent ANC figures such as Nelson Mandela were released from prison. Apartheid legislation was finally repealed on 17 June 1991. In April 1994 the Mandela-led ANC won South Africa’s first elections by universal suffrage.

The immediacy of South Africa’s post-1994 apartheid system was felt in the fabrics of Durban and throughout the encounters we had as we travelled through the townships. The constant use of “post 1994”, as opposed to “the end of apartheid”, suggests that the remnants of apartheid are still present, tangible and have consequences. One of these remnants is the constant racialised distinction between black African Zulus, Afrikaans, Coloureds and Indians. Whilst these communities were in close proximity, I noticed that unsaid expectations, perceptions and tensions were still active in the jokes and attitudes, manifested through relaxed self-awareness.

Climate Change and racialised poverty

The economic legacy and social affects of apartheid still disproportionately effect black and Indian communities. This was most evident on day three of our visit, seeing climate-based community organisers and activists who gathered communities to share their stories of how their homes and lives had been decimated by the floods. Some had been left stranded in community centres since 2009.

We heard from the Indian fishing community who expressed that much of the marine life had been killed by polluted water, and the closure of beaches during lockdown had affected their livelihoods.

We also heard stories from people whose families had primarily died of cancer, because they lived close to chemical power plants, often run by western countries. The intersection of racial injustice and climate change became overwhelmingly clear in this context, and needs to be continually explored in the UK context.

Our visit to these communities decimated by the floods also became complicated spaces of navigating power. As visitors from the United Kingdom, we became acutely aware of the privilege we carried. The people who were struck by these floods and consequently locked into perpetual poverty were looking to us for answers that we could not necessarily give, even though our consumption was linked to their peril.

However, the political act of storytelling gave people agency and a voice to speak against a problem that had been imposed on them. A theological reflection was also given after our visit; a prayer and reflection that God made the sea, but man has made the structures and powerplants that are damaging it.

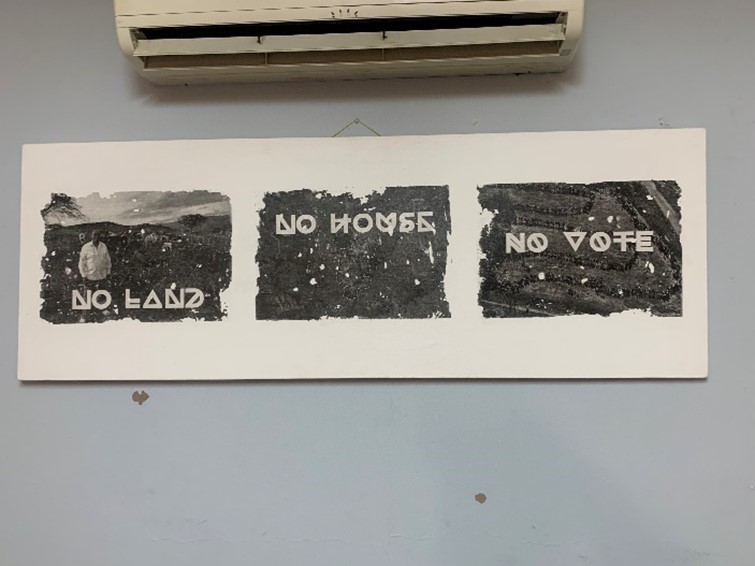

The theme of agency and resistance to external political and environmental forces was also evident on day four, when we visited the Diakonia Centre led by socialist group Abahali Basemjondola. This political group represents the rights of South African shack dwellers whose homes have been decimated by floods, and campaigns for the reclamation of their land, which is a key neo-colonial legacy of apartheid.

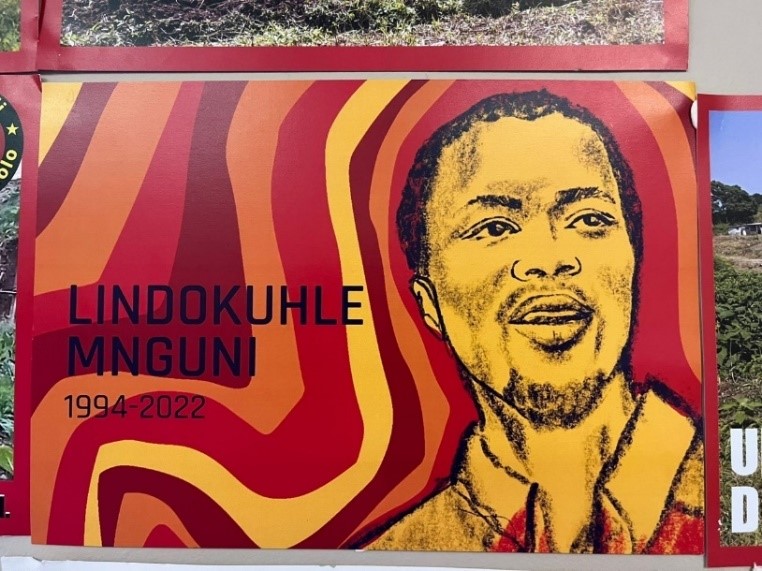

However, their campaign for land has come at a costly price. On the wall we were shown a picture of a millennial adult Lindokuhle Mnguni, who had been assassinated by the local council for standing up for his rights and for the rights of shack dwellers who had been neglected by their government.

This was a powerful and overwhelming moment. This moment also highlighted the immense privilege that young people generally have in the UK to be activists.

We have to stand in solidarity with other young adults in South Africa and across the world whose resistance to injustice is costing them their lives.

The Diakonia Centre also highlighted the lack of political will by the ANC party who took over from the apartheid system in addressing the issue of land ownership.

Judge

Has ecumenism lost its prophetic edge?

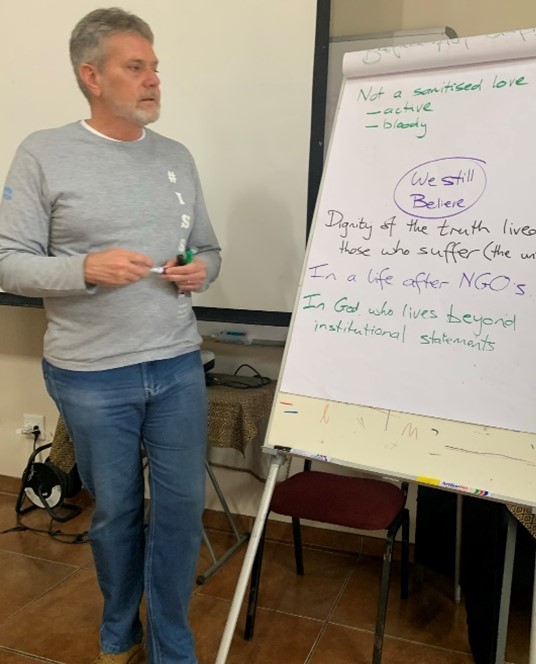

The Diakonia Centre also called out the lack of will by the churches. They explained how the ecumenical movement through the South African Council of Churches was a key force in ending apartheid. Public and private church heroes across South Africa, such as the Anglican priest Desmond Tutu, were prophetic agents in dismantling injustice and are celebrated today.

However, the Centre believes that a shift took place when apartheid ended. Many church leaders got political roles and started to align with the rich and powerful, rather than standing in solidarity with the poor. The focus became about wanting to be seen in the right rooms. Another important change they observed was the move from prophetic justice to unity. Unity became a performative act of compliance and sanitisation, which ultimately made the ecumenical movement loose its voice.

This particularly struck me, leading me to ask: what does this mean for ecumenism in England? Is the focus in aligning with the powerful? Are the rich more valuable than the poor? Are some churches more valuable than others? Is unity a guise for being accepted by society and forsaking the church’s prophetic calling to be with the poor and call out injustice? Has the prophetic dimension of unity been lost?

Other key questions that emerged from our visit to the Diakonia Centre were:

- What is the church for?

- Who is it for?

- Whose church is it?

- God is present, but where is his church?

- Are we building the kingdom, or our denominational and organisational empires?

I believe these are critical questions not only for South Africa, but also for ecumenical movements across the world, including here in England.

Our final stop was a visit to the University of South Africa. Here we met black womanist theologians who use contextual bible study, called ujuma, as a theological tool to understand oppression, and to give agency to oppressed communities to resist their oppression through the text. This tool also helps the perpetrators and those who benefit from perpetration to see how issues of justice also affect them and how they engage in the world. This is a powerful tool that can build relationships and open revelation between communities.

Act

I believe there are some key recommendations for action for our ecumenical context and Racial Justice Working Group (RJWG) at CTE, which we can learn from South African churches and charities. These are:

- To explore what it means to stand in solidarity; to move beyond being an ally (which operates based on one’s self-interest) and towards being a comrade, where we realise the fight against racial injustice is for everyone. Deliverance from racism is for both the perpetrator and the victim, as the imago dei is marred in both.

- To implement the ‘see, judge, act’ methodology and theory of change in CTE’s RJWG work programme going forward.

- To implement contextual bible study in CTE’s RJWG, in collaboration with Christian Aid. Here we can effectively gather different denominations and racial groupings to study together.

- To record the song which I wrote as a piece of music and liturgy for racial justice. This can be explored in the RJWG music and liturgy subgroup, in collaboration with Christian Aid.

- To look at ways of implementing the Church of England’s Difference Course, which allows people to navigate and build relationship through difference in a fragmented society.

- To identify solid links between racial justice and climate change.

- To work with Christian Aid to arrange another trip which others can attend.

- To explore what unity really means and what it means for the ecumenical movement to also be prophetic.