Find out more about ecumenism below, including:

- What does ecumenism look like in England?

- In their own words – ecumenism as described by members of the CTE family

- Receptive ecumenism

- Sharing a Common Life

- Ecumenism and the question of unity – a chapter from the 2017 Theos report ‘That they all may be one: Insights into Churches Together in England and contemporary ecumenism’

- Lead Church model

What does ecumenism look like in England?

Nationally, Churches Together in England brings together more than 50 Member Churches from many diverse traditions.

Locally, churches from a wide range of traditions are working together in many different ways, and there are local Churches Together groups all across our nation. County bodies draw together local Churches Together groups and other local expressions of Christian unity, working ecumenically at an intermediate level.

CTE also works alongside Ecumenical Officers, National Agencies and more than 70 Bodies in Association – a wide range of voluntary groups and charities whose work has an ecumenical dimension, working with Christians of many different traditions.

This page aims to give you an understanding of what it means to work together ecumenically…

In their own words

“At the heart of the ecumenical movement stands the keen desire of Jesus “that all may be one,” and churches around the world for over a century have answered this call through earnest and intentional efforts to overcome historic divisions and to unite in fellowship and service of the coming reign of God.”

“For Ground Level, ecumenism means understanding one another so that we can partner together in expanding the kingdom of God. This means working with churches in all kinds of settings: rural, urban and inner city. Our common aim is to see justice for the poor, and hope for the individuals and for the nation in all that those words mean.”

Richard Bradbury, Ground Level Network (one of CTE’s national Member Churches)

“For me all our ecumenical endeavours are a fruit of Jesus’ prayer: “Father may they be one so that the world will believe…” (John 17.21). I long for the day when we will be one in full and visible unity with a mutually enriching diversity, something I believe can only be brought about by the Holy Spirit.

“Anything Christians of different denominations can do together will contribute towards reaching this unity. I am experiencing that our actions bear fruit when we are working together in a spirit of great love which enables the Holy Spirit to inspire us on how to build unity in our specific situations.”

Elisabeth Hachmoeller, Ecumenical Co-ordinator, Churches Together in the Merseyside Region (one of a network of County Ecumenical Officers across the country)

“Ecumenism is exciting. Ecumenism can take us out of our comfort zone and into a place where not only do we have to listen and share more, but we also have an amazing opportunity to reach out more with the Good news of Jesus. Ecumenism is working with others in your community to build the kingdom of God in perhaps a more respectful and wilder way!”

Yvonne Campbell, General Secretary of Congregational Federation (a CTE national Member Church)

“I’d describe ecumenism as a commitment to living out, incrementally, the vision that Jesus prayed for in John 17; through relationships, prayer and common mission as individuals and churches in all contexts and every level.”

Ben Aldous, CTE’s Principal Officer for Evangelism & Mission

“We all have something to offer, and as Christian denominations we are all in this together. We need to work together for the good of humanity – that’s our mission.”

“Christ is all and in all – God’s Spirit dwells in His people, there is no bond nor free. While some in the past thought that the Spirit was only for the Pentecostals, I understood that the body of Christ is so diverse – we cannot limit the presence of God, He moves in true believers.”

“Paul wrote about the body of Christ with its head and arms – every member has its function, according to what it was created to do… We need to hold on to that unity as the body of Christ, because without unity we cannot change our society. And Christ loves our communities… The more united we are, the stronger we become.”

Pentecostal Bishop Esme Beswick, a CTE President from 2002-2006, reflecting on unity in 2019.

“Unity is not optional. It is built into the very heart of being Christian, for in Christ we become citizens of his kingdom, members together of his body, bound together with all our brothers and sisters across the world. ‘…[Y]ou are’, Peter said, ‘a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, in order that you may proclaim the mighty acts of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light…’ (1 Peter 2:9, NRSV). Mission and unity are therefore inseparable.

“Churches Together in England was founded in 1990 to help the Churches in England explore how they could worship and witness together. During those 27 years the English Christian landscape has changed profoundly – that is reflected in CTE’s growth from 16 members in 1990 to 44 today*. There are many reasons for that: patterns of migration, new forms of spirituality, new ways of Christian discipleship. We are proud to represent that diversity, and eager to find ways in which we can work together in Christ’s name as we respond to the needs and aspirations of our society.”

The Presidents of Churches Together in England, in their preface to the 2017 Theos report ‘That they all may be one: Insights into Churches Together in England and contemporary ecumenism’.

*Update: as of autumn 2023, CTE has 54 national Member Churches.

Receptive ecumenism

Receptive ecumenism is essentially very simple. Instead of asking what other Church traditions need to learn from us, we ask what our tradition needs to learn from them – what we can receive which is of God.

The essence of receptive ecumenism can be encapsulated in the following questions, which Churches are encouraged to ask themselves: ‘what can we learn from each other as Churches?’ and ‘what gifts must we receive from others, recognising that we do not possess everything we need to be faithful, fruitful and fully ourselves?’

Receptive ecumenism is not about diluting or abandoning particular ecclesial identities, but about mutual enrichment, hospitality, listening, and gift exchange: ‘receiving Christ in the other’.

Sharing a Common Life

Many local groupings of Churches working together ecumenically have a regular pattern of joint mission and worship which is important for deepening the relationship between them. Nevertheless, the real challenge of unity is to share a common life; that is, to do together whatever we do not need to do apart.

This goes right back to the Lund Principle, when the third World Council of Churches Faith and Order conference, meeting in Lund, Sweden, in 1952, ‘earnestly request[ed] our Churches to consider whether they are doing all they ought to do to manifest the oneness of the people of God’. It continued: ‘Should not our Churches ask themselves whether they are showing sufficient eagerness to enter into conversation with other Churches, and whether they should not act together in all matters except those in which deep differences of conviction compel them to act separately?’ (Italics ours).

A number of resources were designed to help Churches Together groups and other ecumenical groupings to reflect on different aspects of sharing a common life. Access these on our Sharing a Common Life page.

Ecumenism and the question of unity

Read more about ecumenism in this chapter from the 2017 Theos report ‘That they all may be one: Insights into Churches Together in England and contemporary ecumenism’. The report was based on 63 qualitative interviews, the majority with representatives of CTE’s national Member Churches…

Ecumenism is the effort to express the spiritual unity of the Church and the pursuit of the Church’s greater ‘visible unity’, so ‘that the world may believe’.

Traditionally at the heart of ecumenism lies the issue of Church unity. Ecumenism begins with the recognition that the Church is conspicuously divided and fragmented. This is an uncontested fact that needs little explanation. Theologically, however, ecumenism begins from the fact that the Church is indivisibly ‘one, holy, catholic and apostolic’. Ecumenism stretches between these two conflicting facts, one sociological and the other theological. It is, on the one hand, the effort to express the Church’s unity and wholeness which are rooted in the Tri-unity of God and God’s redemptive work in the world. Yet ecumenism is also the pursuit of the Church’s greater ‘visible unity’ so ‘that the world may believe’ (John 17:21, NRSV).

Another way of putting this is to say that, theologically, unity has two dimensions: gift and calling.

Unity is, firstly, a gift. It is given in the very makeup of the Church as the One Body of Christ (“There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to one hope when you were called; one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.” Eph. 4:4-6, NRSV). This is the Church’s fundamental, spiritual unity. The so-called High Priestly prayer of Jesus for the unity of His followers, recorded in John 17, has, in a crucial sense, been answered in the very constitution of the Church through the pouring of the Spirit. This enduring, spiritual unity is realised and maintained by the Spirit of Christ (“Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace.” Eph. 4:3, NRSV, emphasis added).

Yet this gift of spiritual unity is to be publicly expressed. It is to be lived out and shared with the world, “that the world may believe” (Jn. 17:21, NRSV) and people from every tongue, nation and culture be drawn into God’s Kingdom of light, love, and life. This imperative to express the given spiritual unity, as witness to the world, is intimately related to the ‘calling’ dimension of unity. On this view, unity is also a calling that the Church, in all of its diversity and with all of its differences, is mandated to pursue in order to live out its missional nature faithfully, sent into the world as the Father sent the Son (Jn. 20:21, NRSV).

Features of the English ecumenical landscape

So far we have looked at ecumenism and the question of unity in theological terms. In the following section, we move to look at the current reality, and seek to shed light on the ecumenical landscape in England and CTE.

To say that the picture of contemporary ecumenism in England is complicated is to say very little. It is, nonetheless, to say something true. This is largely explained by the significant changes in the landscape of Christianity in the UK.

While the number of people who call themselves Christian has sharply declined in the last decades, Christianity has become increasingly diverse, with a host of independent, migrant and ethnic minority Churches, mainly from the Pentecostal-Charismatic tradition, springing up and experiencing growth. There is also a wealth of inter-denominational and nondenominational organisations, agencies, and initiatives which are effectively ecumenical. They fulfil some of the traditional aims of ecumenical efforts (e.g. cooperation between different factions of Christianity on specific causes and initiatives), but do not self-identify as ecumenical and, importantly, operate outside traditional ecumenical structures (e.g. ecumenical instruments and their wider networks).

On a broader level, it is fair to say that the traditional models of ecumenism, with top-down structures, and formal dialogues between professionals within hard denominational structures has increasingly given way to a more relational, action-orientated and grassroots form of ecumenism. In the evangelical Protestant world but, importantly for CTE, not in the Catholic or Orthodox worlds, this is coupled with a softening of denominational boundaries.

All of this, in the context of a growing diversity of Christian expression in England makes for an untidy yet vibrant ‘ecumenical scene’. The section below looks in greater detail at this scene, focusing on the different views of unity and ecumenism among CTE members.

Visions of unity and ecumenism among CTE members

The two dimensions of the Church’s unity – as gift to be celebrated and expressed, and as calling to be pursued – belong to the core of Christian teaching. It is important to note that acknowledging the existing spiritual unity of the Church does not preclude the calling to preserve, deepen, and express it publicly. Indeed, the gift and calling dimensions of unity must not be separated or pitted against each other.

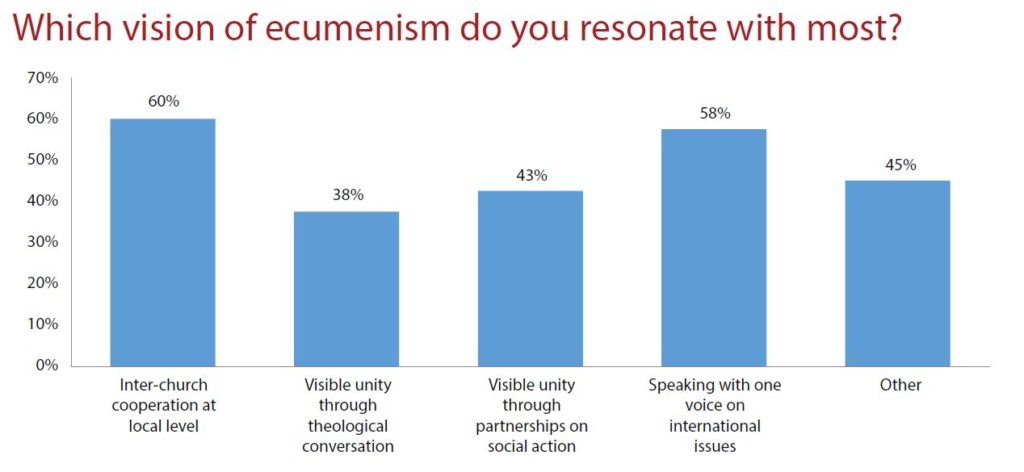

Still, our research revealed that the majority of CTE members place greater emphasis on the ‘gift’ dimension of unity. We heard numerous comments to the effect that unity in Christ is something to be celebrated and expressed practically through collaboration on various aspects of Christian mission and witness. This chimes with what we discovered is a growing appetite for and involvement in practical ecumenism or, as Archbishop Justin Welby calls it, an “ecumenism of action” (see ‘Inter-Church cooperation at local level’ in the graph below), found to be particularly vibrant at the local level.

As a point of contrast, a sizeable number of interviews revealed a general weariness with the ecumenism of previous decades, particularly its formal aspect, which was perceived to be, as one interviewee put it, “hugely lacking in energy”. Indeed, it is fair to say those who placed more emphasis on the ‘calling’ aspect of unity, seeing unity as something to be worked towards and realised, were fewer and seemed resigned to the fact that “reaching visible unity” had turned out to be an elusive ideal.

Receptive ecumenism

Having said that, it is worth noting at this point the growing popularity of the concept and methods of ‘receptive ecumenism’, particularly but not exclusively among those concerned with the ‘calling’ dimension of ecumenism. Reception, according to David Nelson and Charles Raith II, is “one of the most significant concepts for understanding the history and theology of modern ecumenism”. The concept goes back to Cardinal Kasper, President Emeritus of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, while the methodology owes most to Paul Murray, the Professor of Catholic Studies at Durham University.

The essence of receptive ecumenism can be encapsulated in the following questions, which Churches are encouraged to ask themselves: ‘what can we learn from each other as Churches?’ ‘what gifts must we receive from others, recognising that we do not possess everything we need to be faithful, fruitful and fully ourselves?’

Receptive ecumenism, as its advocates stress, is not about diluting or abandoning particular ecclesial identities, but about mutual enrichment, hospitality, listening, and gift exchange: ‘receiving Christ in the other’.

Since 2006 there have been several international conferences on receptive ecumenism. Paul Murray and the Durham Centre for Catholic Studies continue to develop projects to explore the practical outworking of the concept. CTE has also created resources for local use. Our research revealed a general awareness of and, in some cases, a clear commitment to the principles of receptive ecumenism.

Working together

As previously noted, however, the majority of interviewees thought of ecumenism and unity in terms of cooperation, with Churches ‘working together’ on social action at community level. These were keen to note that what has been declining is commitment to a particular institutional-structural understanding of unity and the traditional means for pursuing it. What remains fairly healthy, as the graph below makes clear, is a commitment to a unity that is demonstrated through cooperation between Churches at the local level. The vast majority of Church leaders gave examples of ecumenical partnerships on social action, highlighting personal relationships between leaders as key to this end. More comments on this are to be found in the section on ‘Specific weaknesses’ and the concluding section on ‘Possibilities for the future’.

Which vision of ecumenism do you resonate with most?

Though we found consensus on the relationship between unity and mission (the two fundamental notions of ecumenism), our research revealed no single understanding of what should be the focus of ecumenism. The graph above captures something of the messiness of contemporary conversations about ecumenism. In the questionnaire we devised, representatives of CTE members were asked to select one or more visions of ecumenism with which they resonated. The choices they were offered were gleaned primarily from the interviews we had conducted up to that point.

Sixty per cent of those surveyed identified working together at the local level – most often on social action projects such as food banks, street pastors and homelessness interventions – as the view they resonated with most.

The second most popular vision of ecumenism among our questionnaire respondents was ‘speaking with one voice’ on international issues, such as the persecution of Christians and human trafficking. Indeed, the interviews we conducted throughout the research period revealed a more general appetite for speaking with one voice, primarily but not exclusively through the presidents of CTE. The opportunity and challenge this presents for CTE is briefly discussed in the final section of the report.

Most of the respondents to our questionnaire who selected ‘other’ indicated that they resonated with all the visions put forward and suggested these should not be split apart but seen as complimentary aspects of a ‘rounded ecumenism’.

The mission of the Church within the missio Dei

The majority of interviewees who gravitated towards the ‘gift’ dimension of unity and who emphasised collaboration, almost invariably brought up the topics of witness and mission. Indeed, one of the recurrent themes in the 63 interviews conducted was, unsurprisingly, mission. “Unity is one side of the ecumenical coin, mission is the other”, one interviewee said, stressing that the two should not be separated in thinking about and engaging in ecumenism.

Those who brought up mission referred to it as being not simply a set of activities or practical initiatives that the Church engages in, but rather an active and multidimensional participation in the missio Dei (the mission of God). On this view, the mission of God, to redeem, reconcile and renew the world, establishes and frames the mission of the Church.

Importantly, the Church’s mission consists of, but is not restricted to evangelisation. It includes discipleship, social action, the pursuit of justice, and care for creation.

This holistic and theologically grounded view of mission received a clear articulation at the 1952 International Missionary Conference in Willingen, Germany. Since then it has slowly filtered through the work of ecumenical bodies and denominations across the globe. The findings of our research bear this out. Many interviewees displayed an awareness of this expansive and holistic understanding of mission and wanted CTE to be even more intentionally mission-orientated than has so far been the case.

Lead Church model

In a wide variety of different contexts, the ‘Lead Church model’ can be helpful. It may be one church being the location of a food bank, or a diocese taking a lead on inter faith matters. Whatever the context, a few principles have been formulated.